Provocative Truths

BY BRIDGETTE A. LACY

Crossing back over the Atlantic Ocean from Africa to America. Drawing upon images of slavery, Jim Crow and George Floyd. Commenting on the contemporary world through their art.

These are the things one imagines the seven artists in the crossed kalunga by the stars & other acts of resistance exhibition navigated as they created their work.

“People from the Congo have an age-old belief, that when you’ve died, your soul went with the setting sun to the ocean,” says Roger Manley, the director at the Gregg Museum of Art & Design. “Kalunga refers to edge of the world, a guardian between the living and dead.”

The exhibition features art by seven contemporary artists whose work evidences these types of journeys and their own. Works by José Bedia, Athlone Clarke, André Leon Gray, Esmerelda Mila, Rex Miller, Marielle Plaisir, and Renée Stout share a distinct perspective on how art can speak provocative truths amidst a sea of mutable facts.

Tosha Grantham, the exhibition curator, says the “first part of the show is about the water and second part is what happened on the other side… It may have been a death, a story of survival or resistance. It speaks to immigrants, people who have left their homes.”

Lessons from the Past

Raleigh visual artist André Leon Gray cleverly mines the past in his “What Does Revolution Sound Like?” It features a sketch of Haitian general and former slave Toussaint L’Ouverture on unstretched canvas, with boxing gloves and a rattan chair on a reclaimed speaker box.

It pays homage to a photo titled, “Huey Newton, Black Panther Minister of Defense” by Blair Stapp. The Black Panther leader is sitting in a rattan throne chair wearing a beret and a black leather jacket while holding a shotgun in his right hand and a spear in his left hand.

“The boxing gloves are related to Muhammad Ali, a fight in life’s boxing rings. Below the chair is an empty speaker voice. The idea is there’s no voice for social change for African Americans. It comes and goes,” Gray explains.

“A lot of my work is related to something going on today but also references the past,” he says. “People tend to forget history.”

He reminds us again in “Masters of the Game,” a layered piece that requires close examination to see all the small details of it. It’s described as “chalk on reclaimed chalkboard, acrylic on theater masks, inkjet print on paper, found books, cardboard, antique Eastlake armchair, wooden school desk, petrified chewing gum, teddy bear, hemp twine, ceramic owl figurine, and a feather.”

The work was inspired by “The Deliberate Dumbing Down of America,” by Charlotte Thomson Iserbyt. Gray examines public education and what it means. On one side of the chalkboard, he lays out the pipeline from public education to the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC). He starts with this written on the chalkboard: “Lack of critical thinking makes Jack a dumb boy.”

“I’m not specifically talking about Black kids; I’m addressing the public education system in general but young Black boys feel the brunt of it especially if they come from single parent homes and don’t have father figures in their homes.”

On the floor, books are scattered. “We need to stop playing checkers and play chess,” Gray says. “They are not playing the game correctly. Chess is the ultimate war game. You have to think strategies to win the game. Think logical about things… we as Black people have been conditioned in a certain way.”

Another thought-provoking piece is Gray’s “This is not assimilation, this is faux real,” described as an “acrylic on glass, soil, cotton, cotton branch, vintage football cleats with dried mud, dress shoes, reclaimed wooden ladder, reclaimed chandelier and antique plastic crow figurine.”

What catches your attention are the shoes along the of rungs of a ladder lying flat, the ladder to success. It’s the artist play on Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston’s quote “People can be slave-ships in shoes.”

“They are climbing their way to the top,” Gray explains, but it’s not easy. The chandelier, with a black crow representing Jim Crow, symbolizes the peak. “We went from slavery to reconstruction to Civil Rights. Yet, it’s not what you thought. The bulbs in the chandelier are black and white. We are still segregated in certain ways.”

“Each artist’s work is less about struggle, but more like empowering themselves, coming to terms with injustice, using that as fuel to speak truth to power,” Grantham says.

As she wrote in her exhibition note, “In their own way, each artist gathers and weaves networks of mythologies and contested histories – past and recent – to embed their production with layers of creative, ancestral, and spiritual DNA to elucidate possible futures in formation.”

Artist as Activist

Marielle Plaisir, a French-Caribbean multimedia artist, explores humanity in “The Metamorphose of Ovide,” an acrylic and ink on canvas interpretation of the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a 15-book continuous mythological narrative.

“The narrator changes who he is,” explains Manley. “He transforms several times during the story.” The painting is about magic and transformation, with images of a white dog with wings, fluffy white clouds, a body with emanating vegetation looking like a human turning into a tree and a wizard with a magic wand.

As you take in these artists’ works, you often get the feeling you need a reference book. Their compositions present homework to fully understand the complexity of their work.

And bring your imagination. Manley believes that the gloves on the piece suggests something to help you handle dangerous things, a away of keeping your hands clean.

The mysterious illustration also features Anubis, an ancient Egyptian god of the dead, represented by a jackal or the figure of a man with the head of a jackal. It hints of the shamans.

Plaisir explains that Ovid describes the transformation of the human body and how the Greek and Roman gods were constantly shape shifting into animals, nature and other forms.

“My work shows how we become something better,” she says. “We are able to change our mind to become a better world.”

The Miami-based Plaisir describes herself as an activist artist. She submerges her creations within the borderline of philosophy and sociology, history and memory, to produce mnemonic devices.

In “The War of Troy Will Not Take Place,” an acrylic and ink on canvas piece, she shows a warrior, horses, clouds and chains. It’s her creation of the Trojan Horse hiding Greek soldiers to fight a war.

“That horse looks like its catching fire, exploding,” Manley says. “It resembles a piñata with candy coming out it, but instead women’s jewelry, a colorful handheld fan and a bottle of perfume spew out of it.”

Plaisir explains the war was useless and unnecessary. “My work is about freedom, how we can move freely in this world… it’s about a fight for equality, engaging a dialogue. That’s pretty simple.”

Telling the Untold Stories

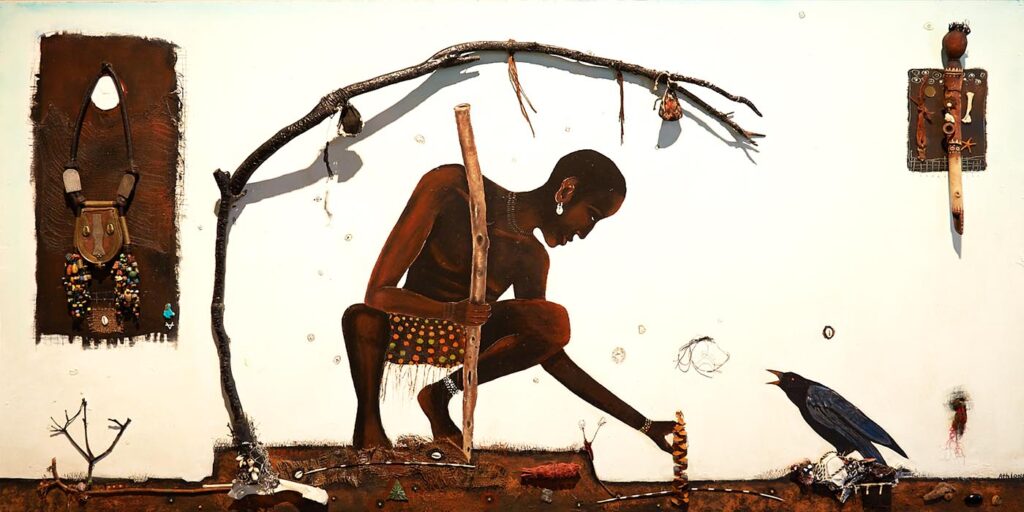

Mixed media artist Athlone Clarke reveals his astute story telling in his pieces. For example, in “Phoenix Nesting, Phoenix Resting,” he portrays a Black woman, sitting in a nest made of fabric and sticks.

“It’s the story of the Phoenix, the bird that rises from the ashes,” he says. “As Black people across the diaspora, we have innate skills of survival. Somehow, we are able to overcome. It might bend us, but it doesn’t break us.”

“She will produce others who will inherit her superpower of bouncing back. It’s a tribute to strong mothers, given their offspring, not just a place of refuge but a place of strength, a place to endure.”

Then in “Lost Diary: Same Root, Different Branches,” Clarke’s amazing mixed media work speaks to how interwoven we are as people. The photo collage features white, mixed race and Black people including couples, children and families.

“It’s hard to find photographs of Black folks, they are not as common as photographs of whites. I see them as these anonymous heroes. They fought the fight in a private, personal way. I can’t have that thrown away.”

Clarke, based in Atlanta, says he enjoys collecting old photographs of people. “I find a way of celebrating people… I thank them for the work they have done.”

In addition to the photographs, he has objects from people’s lives. Things such as buttons, combs, crosses and pocket watches. “I believe objects have energy,” he says. “I compose a piece putting a choir together, if each individual piece is expertly put together, they have one voice. A lost diary of people’s background and struggles.”

“I’m originally from Jamaica, where buttons carry an important significance,” Clarke says. “Buttons are a record of the owner’s life. Sometimes they become fancier. They hold things together. They are used for adornment and to secure.”

Another element of the collage is a folding measuring stick, the type a seamstress would use to measure you for clothing. “I use it because as Black folks, we go through life, feeling like we have to measure up. We have been stripped of our culture.”

Clarke explains sometimes your hair texture, skin color are used against you. “We are are constantly trying to measure up.”

And the cross symbolizes the Christian religion. “We all need different symbols to get us through this very complicated life,” he says.

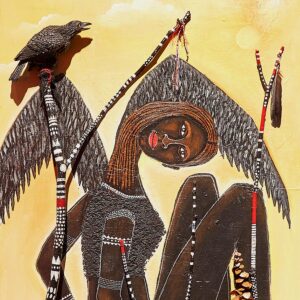

Another one of his intriguing artworks is “Una on the Path Home, Finding Herself.” The mixed media piece on a panel shows a strong woman, an African warrior with hypnotic eyes and tribal marks.

It turns out this pays tribute to Clarke’s mother, who was named Una. “I didn’t know her,” he says. “She died about a year after my birth. She had a weak heart. She had rheumatic fever when she was a child. I felt a sense of debt to her. She gave me life while risking hers. It’s the greatest sacrifice any human could make.”

His art comes from a debt he believes he owes her. “I would see little scrapbooks of her drawings. My grandmother encouraged me to draw and communicate with her. I should at least try to finish her unfinished work.”

All of the artists in their own ways explore issues that force us to reflect. “They are pointing toward solutions,” Manley says. Clarke, Plaisir and Gray are only three of the seven artists featured; Rex Miller and Esmerelda Mila’s mysterious video, Renée Stout’s high-tech African power figures, and José Bedia’s giant Afro-Cuban paintings (one 23 feet wide) also contribute to suggesting other ways to bridge the divide that kalunga and the slave trade so keenly inflicted, and to recover a heritage that was never really lost. Following their leads is both compelling and rewarding for any visitors who come to see the crossed kalunga exhibition.

crossed kalunga by the stars is open in the Adams and Woodson Galleries of the Gregg Museum of Art & Design through March 12, 2022. & other acts of resistance is open in the Black/Sanderson Gallery through February 26, 2022. The Gregg Museum is currently open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday.

Bridgette A. Lacy is an award-winning journalist and author. She served as a longtime features writer for The News & Observer, and is the author of Sunday Dinner, a part of the Savor the South series by UNC Press.

- Categories: